Cinemerica — The lines we draw and the spaces in between

In July of 2015, I was sitting at my desk job counting all the reasons I didn’t want to be where I was. I looked at a map for the one place I had always dreamed of going, the place that felt farthest away from Chicagoland — California.

In five days, I’d managed to go to a place that was at once familiar and yet completely distant from anything I’d ever seen before in my humble, Midwest home, and yet they both feel as American as any place I’d ever been. How could I share a national identity with a place that maintained a different culture, fostered a different economy, and tucked itself into a geography worlds apart?

I started to ask questions about what this thing we call “America” is… about what kind of nation could contain these fundamental differences... how every kid born on the same day as me in California looks outside and calls it the same thing I do: America. I looked at a map of the United States and realized I’d only been to five of them. I saw nearly four million square miles of land, 99.9% of it as foreign to me as the next continent. Like John Steinbeck, “I discovered that I did not know my own country. I had not heard the speech of America, smelled the grass and the trees and the sewage, seen its hills and water, its color and quality of light.”

So began a quest, camera in hand, to find out what this place is that we call “America” — not the global media machine, or the diplomatic super power, but the collection of metropolitan areas, states, and regions on the map that tries to use the same name for “home.” That quest continues to this day, as I make my way through new cities that are compressing and rewiring their cultural DNA in pursuit of progress, while the many lingering frontier lands use their resistance to change to preserve where we’ve been.

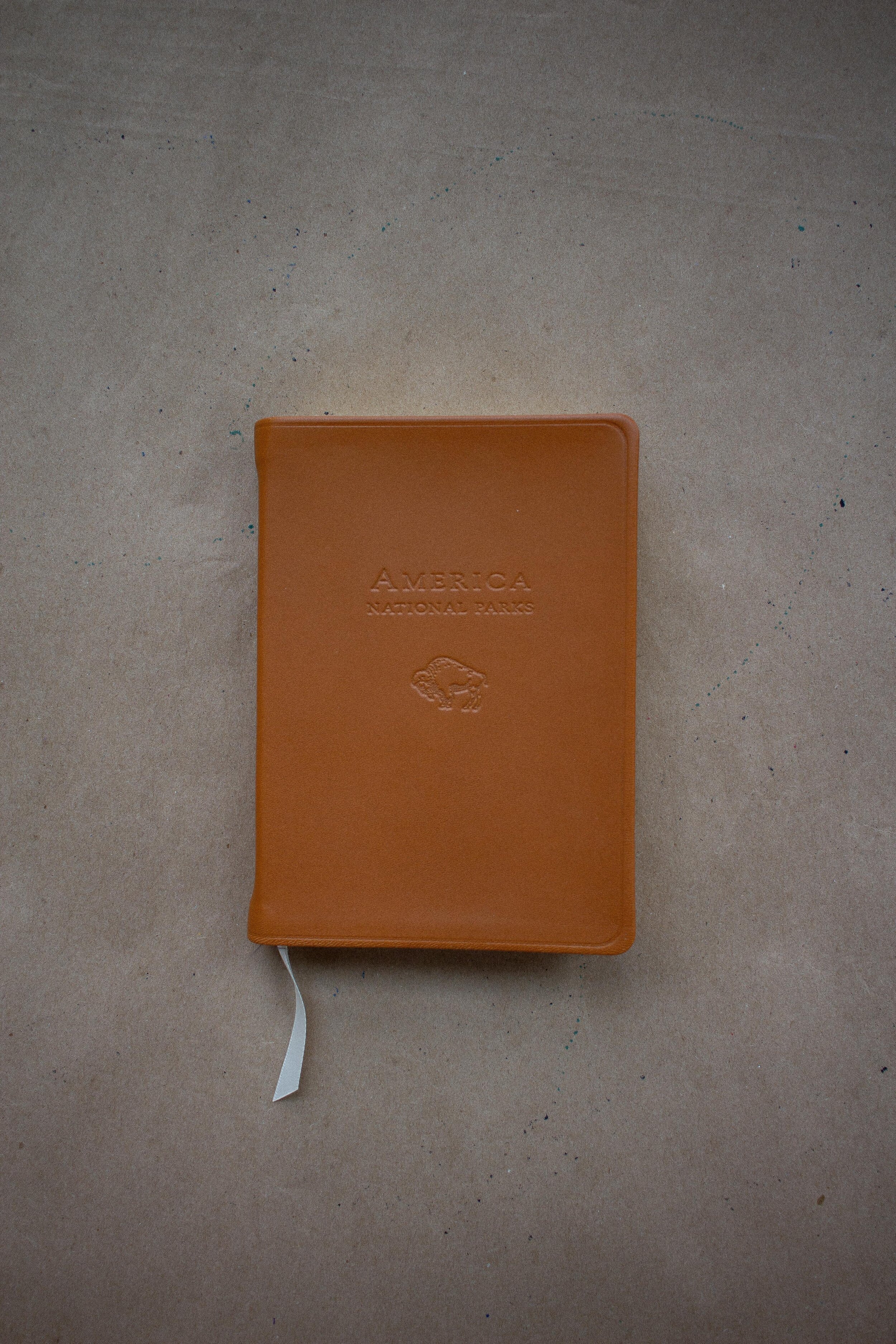

50 states, over 40 national parks, and nearly 100 Airbnbs later, it was at the intersections of nature and culture that I realized what makes America most special, and why empathy is the most essential force we can strive for: Our Union is defined by its differences. I’ve learned that all it takes is a little traveling, even seemingly unambitious domestic travel, to realize that nurture made a deal with nature a long time ago, that the thing you call “you” is defined so immensely by your relationship to the place you’re in. These many territories we have drawn our lines around masquerade as many “Americas.” Everywhere you go, you can hear from people doing their best, people who will welcome into their home people they don’t know, people thinking about going somewhere else, traveling as much as you, if only in their mind.